- Home

- About Us

- Join/Renew

- Member Benefits

- Member Pages

- Log In

- Help

- Museum Store

Had trouble loading images in the original thread that could be enlarged so will try a Part 2.

Purpose here is to run out a scenario whereby the Buffalo businessmen secured a deal with the receivers that allowed Pierce-Arrow continued use of Studebaker bodies, technology and sales channels for some period of time, say 10 or 15 years. I think this was their only chance at survival. The clay models and basic engineering were likely finished prior to Studebaker’s bankruptcy, making a November 1933 launch possible.

First up, Model 829/1229 5-passenger Club Brougham using 119 wb Studebaker Commander body married to 10 inch longer hood and fenders. Using the 1933 Studebaker and 836 pricing as guide, the new entry would have come in around $1,970 and unlike 836A, would have generated a fairly healthy margin. Victoria version could have been fielded if demand warranted

Next up, 833/1233 5-passenger Sedan based on 123 wb President body, which if you recall used the Commander’s 119 wb sedan body with 4 inch longer front doors. Price would have been around $2,260. Convertible Sedan if market demand. Note that Studebaker offered its 2 and 4 door sedans in two rear configurations this year, slant back with no trunk and bustle back with trunk, and both with either a single rear mount or dual side mounts. Pierce could have offered same variety.

Last but definitely not least as the nice ladies with stretched ribbon would have attested, the 848/1248 7-passenger Sedan and EDL with pricing starting at around $2,750. Here the new owners would have needed to invest in 3 inch longer rear doors, either tooled in whole or by welding 3 inch extensions to stock rear doors. Also would have needed 15 inch roof and floorpan extensions. Convertible sedan for parades and the White House.

These and the 833/1233 2/4-passenger rumble seat coupe (shown in original thread) and convertible would have constituted the entirety of Pierce’s showroom for the first 6 months of production. Despite the low investment, the company would have been off to a fast start with nicely tailored, sleek and low, if not exactly eye-popping new cars that were competitively priced and well suited to the dour economic times and concurrent social upheaval. A dose of needed excitement would arrive in April, 1934.

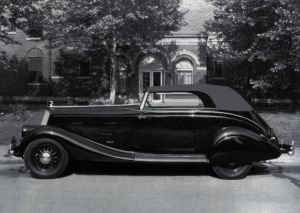

Excitement would indeed arrive in the form of the 836/1236 Silver Arrow. Based on Studebaker’s mid-year Land Cruiser, which came in 119 wb Commander and 123 wb President form (the latter of which again used 4 inch longer front doors), the South Bend cars are often mentioned in same breath as Pierce’s show car. The Buffalo version would have greatly improved the design by virtue of its longer hood. My work-up starts with the President’s body and adds 3 inches to the rear doors to balance the greenhouse proportions, open up the claustrophobic rear and perhaps allow for reclining rear seats. Pricing would have been around $2,650.

The car would have been a critical addition to Pierce’s line-up, assuming the mantle of flagship and representing a genuine style leader with appeal to the “Moderns” as was recently chronicled in The Arrow, and becoming the de facto new Club Sedan.

Compare to the 119 wb Commander version. What a difference 17 inches makes.

Note that the image of the 136 wb Pierce deletes the outer two windows that are part of Studebaker’s 4-window backlight. I felt that the improved appearance far outweighed the marginal visibility that those awkward little windows provided. Also, the car would have been less likely to be confused with a Studebaker when viewed from the rear.

Another possibility would have been a Victoria version on 129 chassis using Club Brougham’s front doors and 2/4-passenger convertible’s chrome windscreen. A fair amount of welding to stitch it all together but no new tooling.

1934-42 pricing and sales projections vs. competition coming soon, stay tuned.

Hello to all and sorry for not following up sooner, auto industry kept me busy with cars of tomorrow so not much time to ponder yesteryear. That said, one must make time to understand history so as not to repeat!

Have 8 graphs dealing with pricing and sales, and lots of images. First will show a few of the images to wrap up the 1934-5 and 1936-7 Studebaker-based cars, then the data download, then more pics.

First image is to point out the easy opportunity the Buffalo businessmen would have had filling out the 34-5 range with cars in between the short and longest wheelbase models. One example is a 140 wb 5-pass with lots of rear seat legroom, accomplished by simply moving the 133 wb doors forward 7 inches with extensions to body no more difficult than what Pierce had already been doing.

Formal sedan on same 140 chassis, using 3 inch longer rear door from 148 wb car and longest front door cut short an inch. Again, no big deal for the body shop and important for Pierce to catalogue all the fine car styles to stay competitive with Cadillac, Packard et al.

And for 1936-7 series, there is some logic in assuming that Pierce might have followed up with the ’34-5 Land Cruiser-based aero sedan, assuming the initial offer had sold reasonably well. This work-up again puts the car on a 136 wheelbase, giving “836” some longevity in the market. Has many of the design characteristics of first series but now, with cab moved forward, ability to dial in more trunk capacity, which the market was increasingly valuing. Image looks hump-backed to my eye but likely would have looked dramatic in the flesh. Backlight is the split V glass from Studebaker’s coupe, in fact the whole rear roof section is taken from that car. Rear quarters also from coupe just as Pierce had done to make the production Silver Arrow. Only a portion of the roof and a unique decklid would have needed tooled, again like production Silver Arrow.

This car may have stood in for the 3-box sedan that I had earlier proposed, that car’s time not yet at hand.

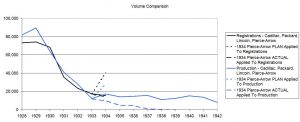

First chart is the big picture. I mainly pulled from the Standard Catalogue but because it contains mostly production data, Brooks I hope you don’t mind my borrowing some registration data from your book on Auburn, Reo et al vs Cadillac et al. Hopefully it will help folks see the interplay between the two, some years production getting ahead of demand, then a correction as shown by the blue and black lines frequently crossing.

The graph shows both the cliff that the luxury market fell off and the stabilization that occurred after 1933. I work in the Buffalo businessmen’s assumption that the market would snap back in 1934 and Pierce would see upwards of 5,000 sales. Applying this uplift to the entire market and focusing on registrations (black dotted line), one can see the extreme optimism the new leadership felt, a critical mistake on their part. Yes, cars were getting old and in need of replacement, but the soup lines were not getting any shorter, and less expensive cars were closing the gap with the fine car field with respect to performance. The production data shows that the industry over-produced for 1934 compared to registrations, so there must have been a general feeing that better days were just around the corner.

I also show what the market would have done had everyone experienced the same sales decline that Pierce did from 1934 on, to illustrate how Pierce lost sales to the field.

Luxury car sales for the big players.

Key take-away’s here are first, that it was initially a two-horse race between Packard and Cadillac/LaSalle, and I show the latter in combined form (green line) to illustrate the point. Second, by 1933 both leaders had taken a severe haircut and Pierce’s market share had increased measurably. It was a new day in the industry the day those businessmen took control of Elmwood Ave, a wonderful opportunity to strengthen Pierce by doing more of the same that had recently been done. Sharing with Studebaker had been working (for Pierce anyway, Studebaker not so much), giving them scale though shared tooling, technology and innovation, and delivering good styling. This is why it was critical to keep it going… or no deal!

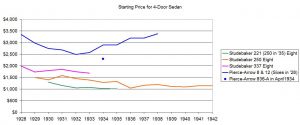

Pricing.

Lincoln entry price was the most expensive for a time, an unsustainable situation that Edsel tried to address, then gave up, opting to do Zephyr instead.

Cadillac/LaSalle achieved a critical price drop in 1934 and the LaSalle about-faced with sleek, low styling and a sharing strategy with lesser GM brands. The market ate it up. I don’t show LaSalle after 1934 because they continued down market below where Pierce would ever compete. I also don’t show the lesser Cadillacs from 1936 on, and break out the ’38 Sixty Special to show its importance in carrying the Senior Cadillacs in these years in sales and competitive pricing.

Packard pricing wasn’t going anywhere so its sales continued the free fall. East Grand Blvd’s only attempt at reduced pricing, the Light Eight of 1932, was a profit failure because it was based on the more expensive Packards, a lesson that should have prevented the Buffalo businessmen from ever attempting the 834A, instead continuing the Studebaker-based strategy that enabled lower pricing AND good margins.

Excepting the 834A, the graph shows another fatal mistake on the businessmen’s part: they increased pricing significantly for 1934. Only Lincoln made the same mistake. That the entry cars took a retrograde step and became wood composite – and taller! – did not help sales either, all things considered.

I included the ’36-7 Cord 810/812 in this and previous graph to illustrate how a hot design could generate strong sales out of thin air, and to remind that those sales could evaporate if the product was deficient.

Pierce vs. Studebaker pricing, all going per plan until 1934 when Pierce and Studebaker parted ways, the businessmen paying $1M to do so. Off plan, things went downhill in short order for Pierce. Pricing, product and production are the key elements to a winning strategy. Success was at their doorstep, if only they had known more about the auto industry. What kind of advise were they getting from the automotive leadership that had been with the company? Apparently not very good advice given the data before them.

Pierce vs. Studebaker sales. Studebaker was the wunderkind of the industry in 1935, the rare case where bankruptcy resulted in success. The big Presidents no longer sold well and were dropped, Pierce passing them by in 1933 despite its much higher pricing. Then as now, brand cache drives sales and profits.

Now we get into projections. First is pricing, assumption being that Pierce remained Studebaker-based, the businessmen insisting on this in return for the $1M… or no deal.

I show against the new senior Studebaker that the Pierce would borrow from 1934 on, and against Cadillac, its prime competitive target.

Pierce would have been right in the hunt, with good cars that were priced right and able to deliver good margins.

And first attempt at sales, not the final but I want to show justification for the turnaround vs. what ultimately befell Pierce. Studebaker sales demonstrate how Pierce’s general styling and technology would have been received in the market. Cadillac’s sales indicate what success looked like for luxury producers putting out great product.

Time to eat! Back to this later.

Tummy full, time for final graph.

Had Pierce charged, some combination of competitors losing sales and segment expanding would have occurred. Given the time, likely more the former than latter. On the other hand, Pierce would have been competing in a slightly lower price range than prior, opening up new prospects new to the marque. Attached graph reduces previous graph’s Pierce sales projections to account for all this. My guess is the actuals would have been somewhere between the two projections.

Sales mostly in the 3,000 – 4,000 range up to the war was enough for good financial health provided that the new owners had gotten to work immediately on streamlining operations, helped by eliminating wood composite construction altogether by close of 1933. Studebaker had already invested millions in the plant, some of which undoubtedly for all-steel body construction, so the heavy lifting had largely been done.

Now a few more pics to justify the sales projections.

The 1938-40 Studebakers were designed in New York City by Raymond Loewy’s design team. Steeply raked windscreens stood and forward projecting hoods and grill with headlights mounted on catwalk for uplevel versions were some of the appearance hallmarks. Vehicle height was lower than previous year and over 5 inches lower than Pierce’s 1934-38 cars. That and beautifully sculpted bodies, sturdy construction and independent front suspension placed these cars in the middle of the arena. For Pierce the game, as prior, was simple: change only what was needed to create an entry car, typically by re-using the Studebaker body shell, then lengthen the shell and tool other elements to create longer wheelbase offerings.

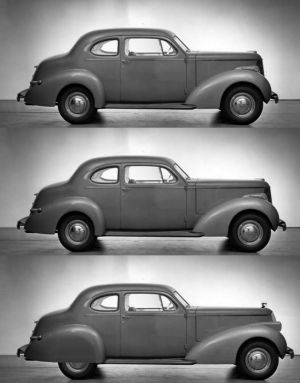

First pic shows Studebaker coupe, the middle car (the President) being the original image resting on 122 wb. The Six and Commander (depicted) sat on 116.5 wheelbase and used same front fenders as President. I added 6 inches to the President to create 128 wb re-appearance of the 1933 Club Brougham. Convertible too, resulting in Continental-style car two years before Lincoln.

Entry 128 wb sedan using Studebaker body shell.