- Home

- About Us

- Join/Renew

- Member Benefits

- Member Pages

- Log In

- Help

- Museum Store

Four inches added to front and rear doors, the front compliments Studebaker’s rumble seat coupe. Roof and floorpan inserts welded in, rear doors tooled anew, 136 wb car with traditional Pierce interior room.

Formal Sedan on same 136 chassis and using same doors, all-in with Art Deco styling. Fender skirts available from Studebaker as would have been the unique decklid and rear quarters, borrowed from Studebaker’s low volume convertible sedan. I suspect that Studebaker had intended to put this decklid style into production alongside its bustle back trunk version but opted out prior to launch because the market had dried up for such designs. Packard dropped its slant back for 1938 too.

Same 136 chassis and doors, now with Club Brougham’s decklid, moving the backlight forward 4 inches. The new Club Sedan.

144 wb 8-pass sedan and EDL. Reused 136 wb doors moved forward 8 inches. Piece of cake for Pierce’s body shop.

Have to include one more because I had recently read some wonderful posts at the AACE forum about Pierce’s V12 and Pierce cars in general vs. competition. Here’s a car that would have beat Duesenberg off the line, in the twisties and on the open road, and still carried a family. Sits on standard 128 chassis, minimalist design including removal of running boards. Priced just under $3,000 in V12 form and weight comfortably below 5000 lbs, would have been good for 120 MPH once engine broken in. Not a catalogue offer but a car that Buffalo would have gladly obliged to create, as it had always done.

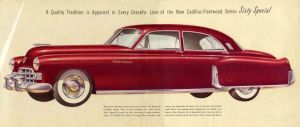

This Caddy would have likely hit Pierce blind-sighted as it did everyone else. First full-out 3-box sedan in America, just in time to keep Cadillac sales healthy during the ’38 recession while everyone else tanked. I’ve tried work-ups for Pierce using convertible sedan’s chromed V-windscreen, sectioning and lowering the car a few inches. The problem is cost to build. Sixty Special started in low $2,000s. Pierce’s response would have been well into the $3,000s.

Helping take Pierce from 1941 on through to immediate post-war period would have been Virgil Exner’s (working for Loewy) fine response to Sixty Special and GM’s follow-up, the 1940 C-bodies. Also available in 6-window form perfectly suited for Pierce lwb cars. Typical of Exner, all was not perfect, in this case the odd rear fenders would have needed scrapped in favor of new tooled versions that looked… normal.

Added 5.5 inches to 124.5 wb President axle-to-dash (11 inches to Commader’s 119 wb, shown).

That will do it for now. Hope you enjoy, and perhaps see some justification in my sales projections based on the fine products that a Studebaker-Pierce sharing arrangement would have produced.

All comments welcome.

Paul

In case the previous image cuts short the Pierce when expanded as it does for me, here’s the Model 1230 by itself.

Also the 1938-40 Model 828 Club Brougham. Used ’36-38 Pierce front design for this and ’41 series not knowing what the designers had actually planned. A nice classic design.

The economics you present would have saved the company while losing

the traditional customer. Of course we know what happened as a result

of catering to the traditional customer. The Studebaker frames were

stout, but designed to accommodate quite a bit less torque and about

3,600 lbs. Wheels and tires would need upgrading. Gas mileage was

Studebaker’s strong point and would be halved by using Pierce engines

and the beefing up necessary for the new product. I bought a’39 Cad

Model 61 with my newspaper money when I was 16.I promptly raced ’50’s

cars at stoplights on El Camino. I wiped out most stock cars even

though I had a slipping clutch. The car was Cad’s cheapest, lightest

(3’800 lbs.), with it’s highest horsepower engine(135 hp except model

75).That engine was quiet, fast and durable. The suspension was soft

and would dip when you applied the brakes and it did not corner well.

My ’37 Studebaker has Planar suspension (transverse sprung like a Cord

or Ford, with independent suspension)which is superior to the Cad in

comfort and handling. The ’38 President was offered with a Borg-Warner

vacuum shift(like the Cord),they named it “The Magic Hand””. Thanks for

looking into the future of the past.”

Amazing study; Packard did make it a while longer on the 120 and 110; Buick threatened Cadillac all through the 1930s and early 1940s with their Limited; just look at Mercedes-Benz today and their work with the C-Class in the USA.

One wonders if Pierce-Arrow had been more widely represented (more dealers, with a higher-volume model; if management had seen fit to make it until war orders came in; if someone’s name had been on the building, like Ford in recent years: when they were able to barely avoid bankruptcy as GM and Chrysler went down, it was said that the fact there were Fords who simply could not allow it to fail made the difference.

One realizes also that average cars were getting so much better in quality of performance and reliability that they were closing the gap with hand-made and near-hand-made cars at the middle-high to high end of the market, and the technology was increasing in complexity and costs such that only the high volume of mass production and sales could support the overhead needed for engineering and tooling. It seems that it was a change destined to drive the classics into history. Of course the classics still had the cachet and still have it today!

Paul,

I agree with Tony and Randy – your “looking into the future of the past,” as Tony has expressed, is a really enjoyable diversion, thank you.

And on the subject of what-if?

Both Packard people & Packard publications spend much time on the what-if’s: What-if still cash-rich Packard hadn’t merged with the failing & broke Studebaker in 1954?; what-if Packard had had an overhead valve V-8 plus a Coupe deVille-like hardtop styling in 1950?; what-if every single car sold during the seller’s market of 1946-47 (with materials shortages and post-war steel allocations limiting production) had been a high-margin, high-profile Custom Super Eight? (instead +50% of unit production was allocated to lower-priced & lower-margin models including 6 cylinder taxi cabs); what-if Packard had purchased Hydra-Matics from G.M. as Lincoln, Kaiser-Frazier, Hudson and Nash all did and utilized their offsetting cash and R&D resources to hasten development of a V-8 engine – instead of further spending on development of their reputation-damaging Ultra-Matic? What-if?

Now, move the “what-if” 250 miles East of Detroit to Elmwood Ave. in Buffalo:

What-if Pierce were able to hang-on until 1940? Most certainly with the start of the War in September, 1939, and with the U.S. Military armaments build-up, lend-lease, Allied production contracts, etc., Pierce would have survived until V-J Day in 1945 – and most likely with sizable accumulated profits giving their balance sheet a stable foundation for post-war development of new models and engines. Beyond 1945 and into the 1950’s, who knows? That’s where Paul’s artistic what-if’s cause one to read and wonder. Thanks again!

The artistic renderings are fascinating; the possibilities are endless I suppose.

I wonder if Pierce-Arrow’s management and leaders simply were unable to think “down market”? If they could not envision an existence in the larger market and so did “what we have always done” until The End? So many companies do this because they simply can’t change enough to make a positive difference. This level of change seems to require someone from the outside, like “Chainsaw Al” to get things going in another, hopefully more positive, direction.

I saw a Cadillac this morning on my way to the office; it seems that Cadillac hardly matters any more, compared to what it once represented in America and the world: a car people really aspired to own if they were ever able to afford one. Years ago, even if a person might be able to buy one, it was a little off putting to some people to own one: like they really didn’t deserve it, or like they were “putting on airs”. So they bought a Buick.

My Dad stated flat-out in the early 1970s that he was not about to pay $6000 for any car; the Buick Electra 225 had become the car of choice among the locals and that’s about what it took to bring one home. He was offered a new Cadillac for $6500 and would not go there, so he bought a year-old Electra for $4000.

Cadillac and some of the other brands like Buick have lost a lot.

Glad you guys enjoyed the what-ifs, was something I have long wanted to tackle.

The history suggests that Studebaker and Pierce were, in some respects, more forward thinking even than GM, sharing body panels across a price range far broader than any company was doing at the time… and getting away with it!

For example, the 1933 rear door is identical between Six, Commander, President and 836/1236 (excepting 139 wb cars, which are 3 inches wider), differing only in location relative to rear wheel. Panels and sometimes whole bodies were shared between South Bend and Buffalo, as PAS has long known.

The question of whether Pierce need have lost its traditional customer is a critical one, and may have largely been answered with the 1933 836/1236, which not only shared extensively with Studebaker as had been the case for several years prior, but had switched to Studebaker’s all-steel construction and lower frame, hood and roof line. As we learned in recent Arrow issue, some buyers perceived these cars to be louder over bumps and when closing doors. The fact that almost 90% of Pierce’s 1933 buyers bought these sleek all-steel cars instead of the taller wood-composite 1242/1247 indicates that most of Pierce’s traditional customers found the rebalanced attributes to be acceptable, perhaps even an improvement given Pierce’s increased market share in 1933. Perhaps the question becomes, was the 836/1236 a luxury car in the fine car tradition? I think yes, the cars still having the build quality, performance, comfort, styling and proportions associated with such cars. These would have continued.

For the what-if 1934-42 models the only change I made to the 1933 sharing strategy was addition of a slightly lower priced model to respond more directly to the Depression, akin to Pierce in 1933 having used the shorter Commander/President 82 rather than longer President 92 body for its entry car. As my good friend and auto history teacher, Steve Kelly suggested, the cars could have been powered by the 340 or 366 Eight rather than the 385, and used Studebaker’s strengthened long wheelbase hearse frame and suspension. The cars would have been nothing like the down market Packard One Twenty, and being double that series’ price and much more elegant, would likely not have tarnished Pierce’s good name, allowing the company to continue to advertise, albeit with a stretch, that it was the one manufacturer exclusively devoted to fine car production.

We can surmise a few things about Pierce post-war. Have been busy of late creating visuals so if you are game, join me for a ride!

I can’t imagine Pierce surviving the late 1940s through say, the 1970s without basing its bodies on mass produced offerings. Lincoln tried to make a car of Pierce-Arrow quality in 1956, the Continental Mark II. Being only a coupe and of unique body and frame, it failed to generate the sales and margins needed to cover its investment. Cadillac tried the same thing in 1957 with its close-coupled 4-door hardtop Eldorado Brougham, with same result. Only when sharing body stampings with lesser models and brands did these two marques make money, and in the case of Lincoln and Imperial, even this too often proved elusive due to styling and other deficiencies.

For Pierce, the question of who to team with would have become the constant existential challenge, or rather, opportunity if looked at positively. I think the company would have needed to arrive at the post-war party with two things: a strong name that any lesser manufacturer would have welcomed association with, and – Stuart’s astute comment notwithstanding – an automatic transmission, which had Pierce survived would have been the follow-on to the semi-automatic transmission that it would gone on to develop in the late Thirties rather than selling its patent. How demoralizing it must have been for Henry Ford II to have asked GM for its transmission! Steve Kelly has suggested that all the Independents should have worked with Borg-Warner to produce an automatic, an excellent suggestion. Pierce would have likely been the lead program, needing the unit for its first all new post-war design to be competitive with Cadillac.

What design, you may ask? And when? This would have depended on the partner. Let’s explore a few.

First we have to identify Pierce’s post-war competitive set. This is easy because there was only one car! The Cadillac Sixty Special, which was all new in Spring, 1948. It was 12 inches longer than the Series 62 upon which it was based and with a 7 inch longer wheelbase, and had an important new design innovation: a long decklid married to a long rear overhang. Pierce’s designers would have needed to grasp this opportunity on its own, concurrent or prior to Cadillac’s design team.

As you may be aware, Studebaker stopped making its large cars after the war, determining that its small pre-war Champion was sufficient to carry the company reconstituted as the industry’s first post-war model with “The New Look.†Let’s assume that Pierce would have continued to make its large pre-war Studbaker-based cars, continuing to buy stampings from, I think, Budd out of Philidelphia. Or was it Briggs that Studebaker used? I’ll need to double check.

In late 2015 I shared with this forum a fictitious story about a little boy and his father who purchased a post-war Pierce V12 sedan based on Hudson’s step-down. Collaboration with that respected company would have been one option for Pierce, advantages being that Hudson was working on a revolutionary new unibody car of high strength and low overall height. Disadvantages would have been list of styling/proportion deficiencies in the basic design sufficient to force Pierce to undertake expensive remediation that included reworking of the Mono-bilt space frame and expensive redesign of assembly operations to modify and build out the frame. Additionally, there were personalities involved, in this case stubborn Edward Barit in control of Hudson. While his faults did not become fully apparent until the early 1950s, his embrace of Step-Down’s deficient styling might have been cause for early concern on Pierce’s part, a warning sign.

Here’s a Hudson work-up that uses more Hudson stampings than what I showed in the image accompanying the fictitious story. Pierce’s designers would have grasp the inherent goodness in the Hudson coupe’s proportions, using the those stampings as starting point for its sedan. My work-up adds 8 inches to the coupe’s roof and 4 inches to the front axle-to-dash (aka, hood). Reuse of coupe’s decklid in its entirely would have saved money and, mated to longer roof, would have increased rear overhang by 8 inches, making the car fully competitive with Sixty Special. To decrease Step-Down’s claustrophobic interior and “heavy looking†appearance, its beltline could have been cut down in the greenhouse area and hood made flatter.

Coupe, convertible and long wheelbase 8-pass car, or perhaps “longish†wheelbase 6-pass car for chauffeured executives could have been offered. I have an image but won’t burden you with it.

Pierce was oh so close to being a viable part of the war effort. If one reads the book “Freedom’s Forge” by Arthur Herman (and I highly recommend it, it details the leaders of the automotive giants helping the war effort), one will see that preparations for entering WWII began well before the US actually entered the war. Had Pierce just had decent 1938 sales, and gotten into calendar year 1939, things might have been different.

Just imagine, three Pierce V-12’s powering a PT boat! Yes, reality was that Packard supplied the trio of engines for each PT boat, but Packard could have been second runner up!! The throaty roar of a Pierce V-12 powered Mustang P-51! Sherman tanks….and the list goes on…..

Woulda Coulda Shoulda….doesn’t your heart skip a beat seeing the attached picture (not a new catalog, unfortunately, rather a school yearbook!)…

I also thought about a tie-up with FoMoCo, the all-new 1949 Cosmopolitan offering “good bones†aesthetically, and of body-on-frame construction so no major tear-up to Elmwood Avenue. Lincoln planners might have been interested not only in the automatic transmission but the larger type car that it wanted to produce but couldn’t afford. A Pierce-badged version might, in the eyes of Lincoln marketers, have conferred additional prestige on the Cosmopolitan, better positioning i against Cadillac’s least costly models while Pierce’s version battled Sixty Special. Alas, I wonder if Pierce leadership would have felt they were making a deal with the devil, Dearborn threatening to become ever more possessive and a new fiefdom tantalizing up-and-coming ambitious Ford, Mercury and Lincoln executives.

Have run out a few Lincoln and Mercury-based Pierces into the Fifties and Sixties but for this discussion will present a simple walk from Cosmo to 3-box sedan. The car ended up 5 inches longer than the Caddy, making it a real beast! But such was needed to bring it into good proportion.

Another way to look at these work-ups is to see them as opportunities that Hudson and Lincoln had for their own cars.

Good thoughts David, thanks for sharing. Pierce would have contributed greatly to the war effort, that much is for sure. Will keep the book in mind next time I ask Santa for a present.